Answer: Chemistry, music, and golden retrievers. Question: What are some of Gary Keck’s passions?

|

| Professor Gary Keck with musician Merle Haggard, after whom Keck has named several compounds |

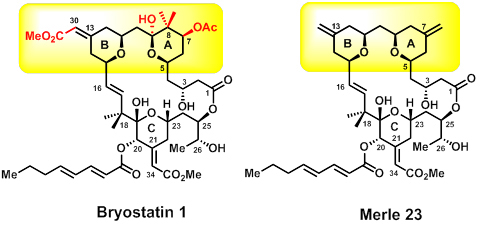

We didn’t get to golden retrievers, but music – especially country music, and especially that of Merle Haggard – surfaced a few times in my chat with Gary Keck, Distinguished Professor of Organic Chemistry here at the U, and 2014 Arthur C. Cope Scholar Award recipient. I found that one needn’t look hard to find a little music/chemistry cross-pollination in Keck’s work: his efforts to synthesize the natural products known as bryostatins have led to a series of analogues that he’s dubbed “Merle compounds.”

But there’s nothing frivolous about Merles, or bryostatins. Bryostatins are compounds found in marine organisms – tiny filter-feeders known as bryozoans – that have been thought for decades to have cancer fighting potential. More recently, they’ve shown signs of possible effectiveness against HIV and Alzheimer’s disease. However, the flagship compound, bryostatin 1, required tons of marine animals to yield just grams of the compound, hence efforts by researchers like Keck to provide access to these materials by total synthesis. Here Keck and his group provided a new asymmetric pyran synthesis termed “pyran annulation”, as well as an effective overall strategy for bringing together two complex subunits using this process. In 2011, Keck and his co-workers achieved the first total synthesis of bryostatin 1.

|

| Translocation of fluorescently tagged PKCs after exposureto the phorbol ester PMA (left) or bryostatin 1 (right) |

Bryostatin 1 is able to modulate the activity of enzymes in the family known as protein kinase C (PKC). Intracellular PKC signaling governs critical metabolic activity, including cell replication, differentiation, and death. Some PKC activators, notably phorbol esters, trigger PKC responses that can promote rapid tumor growth. Bryostatin 1’s binding to PKCs is similar to that of phorbol esters, but in contrast it does not promote tumor growth, and can effectively block the action of phorbol esters. Encouragingly, in some in vitro studies it induced apoptosis (cell death) in tumor cells. However, that effectiveness has not yet been replicated in clinical trials using human patients.

To illuminate the connection between bryostatin activity at the molecular level and biological responses at cellular and higher levels, Keck notes the importance of studying analogues. His group has shown that small variations in bryostatin structure can lead to very different cellular responses. For example, fluorescently tagged PKCs can be watched as they translocate within a cell, in response to different activators. Translocation differences, in conjunction with other kinds of detailed biological characterizations, can help in deconstructing processes that Keck likens to a Rube Goldberg machine. Though in this case it’s more like a “twenty-story building full of Rube Goldberg machines, all interacting with each other,” Keck says.

More analogues means more tools in the toolbox for tinkering with that machine; enter the Merle compounds. Keck and his team have synthesized these bryostatin kin with various simplifications and substitutions. An example is Merle 23, another potent PKC binder, which has a similar structure to bryostatins but gives biological responses more like those of a phorbol ester. Its structural differences from bryostatin 1 help to identify which features of that molecule are responsible for the distinctive biology associated with bryostatin 1.

While I digest this overview from Prof. Keck, he browses for images on his computer to show me models of bryostatin/Merle variations and micrographs of tagged-PKC translocation results. Along the way, he proudly displays photos of his all-access pass to Merle Haggard shows, and of him and Merle in front of Merle’s touring bus. “He calls me ‘ol’ Gary’. Which, by the way, is not the same as ‘old Gary’.”

I imagine ol’ Merle is pleased to have namesake compounds that may someday unlock treatments of cancer, HIV, or Alzheimer’s.

Story by Paul Bernard